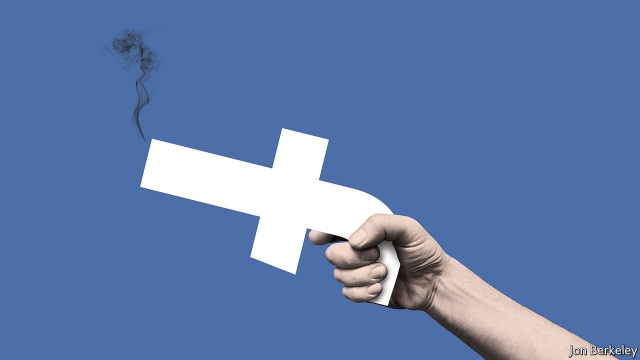

Recently, The Economist released their new issue featuring a cover image of the Facebook symbol stylized as a gun, along with the title “Social media’s threat to democracy”. This cover represents, in a single and powerful image, the rising opinion that social media has been weaponized and turned against us. Meanwhile, the title explicitly states that it is a threat to democracy (although the cover article in the issue actually poses this as a question rather than a statement, “Do social media threaten democracy?”). As a scholar of social media, I find this very interesting. It was not long ago that people were praising social media as force for democratization, helping marginalized and oppressed populations voice their grievances and resist oppression. I recently published a blog post about this, describing how online spaces and free culture are helping to build a new, although imperfect, digital public sphere.

Recently, The Economist released their new issue featuring a cover image of the Facebook symbol stylized as a gun, along with the title “Social media’s threat to democracy”. This cover represents, in a single and powerful image, the rising opinion that social media has been weaponized and turned against us. Meanwhile, the title explicitly states that it is a threat to democracy (although the cover article in the issue actually poses this as a question rather than a statement, “Do social media threaten democracy?”). As a scholar of social media, I find this very interesting. It was not long ago that people were praising social media as force for democratization, helping marginalized and oppressed populations voice their grievances and resist oppression. I recently published a blog post about this, describing how online spaces and free culture are helping to build a new, although imperfect, digital public sphere.

But public attitudes towards social media turned sour this week as Facebook, Google, and Twitter were grilled by the U.S. Congress in a series of public hearings about Russian interference in the 2016 Presidential election. For the first time, Facebook revealed thousands of online targeted ads which it discovered were purchased by Russian-linked accounts. These ads showed a disturbingly sophisticated understanding and targeting of American cultural divisions, and worked by playing both sides against each other. The goal, presumably, was to sow the seeds of discord and undermine confidence in our social institutions and in democracy itself. There is no doubt now that Russians did indeed interfere with our 2016 Presidential election. This is serious business which needs to be addressed.

But what exactly is the remedy we need? The current attitude on Capital Hill, and quickly spreading around the U.S., is to scapegoat social media companies. Senator Dianne Feinstein, California (D), placed full blame on the tech companies for Russian interference. “You bear this responsibility,” she said. “You’ve created these platforms.” However, as an insightful op-ed in The New York Times pointed out, “we, the users, are not innocent.” The article goes on to say, “Facebook and Twitter are just a mirror, reflecting us. They reveal a society that is painfully divided, gullible to misinformation, dazzled by sensationalism, and willing to spread lies and promote hate. We don’t like this reflection, so we blame the mirror, painting ourselves as victims of Silicon Valley manipulation.” We are still, as Guy Debord famously critiqued in 1967, “The Society of the Spectacle”.

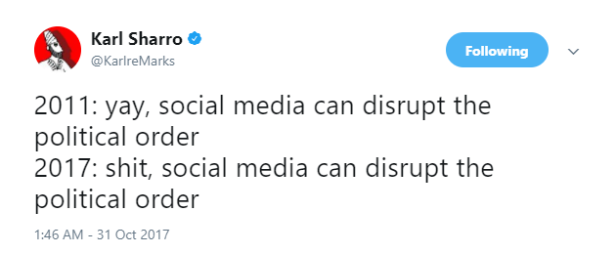

The disruptive nature of social media was exactly what we loved about it back in early 2010s when it was being used in popular uprisings against authoritarian states in Tunisia, Egypt, Turkey, Spain, Ukraine, and Hong Kong. Now its affordances are being put to use by different players. Social media itself is not the problem, it is only a tool. Our tools simply reflect our existing social divisions. They did not create them.

That being said, social media in its current forms may function to magnify, and even encourage, those divisions. As one recently article argues, there has been a growing “epistemic breach” in the U.S. for quite some time. As a culture, we no longer agree on the most basic premises of “what we believe exists, is true, has happened and is happening.” This began decades ago with “the U.S. conservative movement’s rejection of the mainstream institutions devoted to gathering and disseminating knowledge (journalism, science, the academy) — the ones society has appointed as referees in matters of factual dispute. In their place, the right has created its own parallel set of institutions, most notably its own media ecosystem.” This started with right-wing radio in the 1980s, Fox News in the early 2000s, and has now become website like Breitbart and Stormfront. Research shows that these far-right partisans make up one side of the polarized media lanscape, while the mainstream media has become dominated by left-center ideology.

This polarization of the media and of U.S. society in general has grown significantly in just the past couple of years. Techno-sociologist Zeynep Tufecki argues that the ad-based business model of current social media is all about getting the most clicks, which in practice ends up creating a spiral of increasing extremism and radicalization. This is because after a person has, for example, watched one video on Youtube, they are more likely to continue watching videos if the next suggested video is even more shocking or extreme. This is how algorithms are designed to hold users’ attention. “It’s like you start as a vegetarian and end up as a vegan,” she describes.

But how exactly these algorithms work is completely unknown, despite the fact that they clearly have tremendous influence over how we think by manipulating what information we are exposed to. These algorithms are proprietary, and furthermore, the inner workings of companies like Facebook, contrary to its stated mission to “make the world more open and connected”, are notoriously opaque (as powerfully revealed in the Dutch documentary Facebookistan). These companies act with no accountability, as if they are their own “net states” beyond any jurisdiction but their own.

So, what should we do?

Scapegoating social media companies may be easy and feel good for now, but it is a dangerous path to take. Doing so gives states the opportunities to step in and impose their own control for the sake of “national security”. As Senator Tom Cotton, Arkansas (R), stated during this week’s hearings, “Most American citizens would expect American companies to be willing to put the interests of our country above, not on par with, our adversaries, countries like Russia and China.” But social media platforms are supposed to be free and open, not outlets for state interests. Some argue that these platforms have already begun edging towards this path by abandoning their own neutrality policies to ban white supremacist websites and accounts. While few would defend white supremacists, such actions open the door to tech companies taking sides in cultural conflicts, such as choosing to support the agenda of one state over another, or even one political party over another. This is a dangerous precedent.

Be that as it may, the secrecy and opacity of Facebook, Google, and other social media is certainly problematic. More than anything, we need transparency and public accountability if we want social media to be a positive component of the digital public sphere. Habermas, the progenitor of the concept of the “public sphere”, warned that while there is a real value to the openness social media can bring, especially in restrictive societies, it could also potentially erode the public sphere in democracies.

So how can we reform social media whilst protecting the public sphere? According to Ben Peters, when considering Internet reformation, “perhaps no initial task is as consequential as the questions we ask and how we formulate them.” Some have proposed we treat social media as a “public utility” rather than a for-profit enterprise. But this could involve governments taking control, which may fly dangerously close state-imposed agendas (the recent FCC threats to repeal Net Neutrality speak to this possibility). Tufecki argues that we need to reform our entire digital economy away from ad-based incentives. Though these ideas could be effective, they are seen as by extreme by some. Perhaps the most thoughtful and comprehensive list of reforms I’ve seen so far comes from a recent report by the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School entitled “Information Disorder: Towards an interdisciplinary framework for research and policymaking”. It provides not only a rich theoretical explanation of the problem of “information disorder” (e.g. “fake news”), but a thorough list of 35 recommendations for tech companies, national governments, media organizations, civil society, education ministries, and funding agencies.

One of the best aspects of this list is that it does does not place full responsibility for our current problem on any one lone party. There are no simple solutions here, but we must be careful in defining the actual problems, in all of their nuance and complexity, and seeking the best solutions for society with distorting or destroying to very value that these social media provide.

Below is the full list of recommendations:

What could technology companies do?

- Create an international advisory council. We recommend the creation of an independent, international council, made up of members from a variety of disciplines that can (1) guide technology companies as they deal with information disorder and (2) act as an honest broker between technology companies.

- Provide researchers with the data related to initiatives aimed at improving the quality of information. While technology companies are understandably nervous about sharing their data (whether that’s metrics related to how many people see a fact-check tag, or the number of people who see a ‘disputed content’ flag and then do not go on to share the content), independent researchers must have better access to this data in order to properly address information disorder and evaluate their attempts to enhance the integrity of public communication spaces. As such, platforms should provide whatever data they can—and certainly more than they are currently providing.

- Provide transparent criteria for any algorithmic changes that down-rank content. Algorithmic tweaks or the introduction of machine learning techniques can lead to unintended consequences, whereby certain types of content is de-ranked or removed. There needs to be transparency around these changes so the impact can be independently measured and assessed. Without this transparency, there will be claims of bias and censorship from different content producers.

- Work collaboratively. Platforms have worked together to fight terrorism and child abuse. Slowly, collaboration is also beginning to happen around information disorder, and we encourage such collaboration, particularly when it involves sharing information about attempts to amplify content.

- Highlight contextual details and build visual indicators. We recommend that social networks and search engines automatically surface contextual information and metadata that would help users ascertain the truth of a piece of content (for example automatically showing when a website was registered or running a reverse image search to see whether an image is old). The blue verification tick is an example of a helpful visual indicator that exists across platforms. We argue that technology companies should collaborate to build a consistent set of visual indicators for these contextual details. This visual language should be developed in collaboration with cognitive psychologists to ensure efficacy.

- Eliminate financial incentives. Technology companies as well as advertising networks more generally must devise ways to prevent purveyors of dis-information from gaining financially.

- Crack down on computational amplification. Take stronger and quicker action against automated accounts used to boost content.

- Adequately moderate non-English content. Social networks need to invest in technology and staff to monitor mis-, dis- and mal-information in all languages.

- Pay attention to audio/visual forms of mis- and dis-information. The problematic term ‘fake news’ has led to an unwarranted fixation on text-based mis- and dis-information. However, our research suggests that fabricated, manipulated or falsely-contextualized visuals are more pervasive than textual falsehoods. We also expect fabricated audio to become an increasing problem. Technology companies must address these formats as well as text.

- Provide metadata to trusted partners. The practice of stripping metadata from images and video, (for example location information, capture date and timestamps), although protective of privacy and conservative of data, often complicates verification. Thus, we recommend that trusted partners be provided increased access to such metadata.

- Build fact-checking and verification tools. We recommend that technology companies build tools to support the public in fact-checking and verifying rumors and visual content, especially on mobile phones.

- Build ‘authenticity engines’. As audio-visual fabrications become more sophisticated, we need the search engines to build out ‘authenticity’ engines and water-marking technologies to provide mechanisms for original material to be surfaced and trusted.

- Work on solutions specifically aimed at minimising the impact of filter bubbles:

- Let users customize feed and search algorithms. Users should be given the chance to consciously change the algorithms that populate their social feeds and search results. For example, they should be able to choose to see diverse political content or a greater amount of international content in their social feeds.

- Diversify exposure to different people and views. Using the existing algorithmic technology on the social networks that provides suggestions for pages, accounts, or topics to follow, these should be designed to provide exposure to different types of content and people. There should be a clear indication that this is being surfaced deliberately, and while the views or content might be uncomfortable or challenging, it is necessary to have an awareness of different perspectives.

- Allow users to consume information privately. To minimize performative influences on information consumption, we recommend that technology companies provide more options for users to consume content privately, instead of publicizing everything they ‘like’ or ‘follow.

- Change the terminology used by the social networks. Three common concepts of the social platforms unconsciously affect how we avoid different views and remain in our echo chambers. ‘To follow’, for most people subconsciously implies a kind of agreement, so it emotionally creates a resistance against exposure to diverse opinion. ‘Friend’ also connotes a type of bond you wouldn’t want to have with those you strongly disagree with but are curious about. So is the case with ‘like’, when you want to start reading a certain publication on Facebook. We should instead institute neutral labels such as connecting to someone, subscribing to a publication, bookmarking a story, etc.

What could national governments do?

- Commission research to map information disorder. National governments should commission research studies to examine information disorder within their respective countries, using the conceptual map provided in this report. What types of information disorder are most common? Which platforms are the primary vehicles for dissemination? What research has been carried out that examines audience responses to this type of content in specific countries? The methodology should be consistent across these research studies exercises, so that different countries can be accurately compared.

- Regulate ad networks. While the platforms are taking steps to prevent fabricated ‘news’ sites from making money, other networks are stepping in to fill the gap. States should draft regulations to prevent any advertising from appearing on these sites.

- Require transparency around Facebook ads. There is currently no oversight in terms of who purchases ads on Facebook, what ads they purchase and which users are targeted. National governments should demand transparency about these ads so that ad purchasers and Facebook can be held accountable.

- Support public service media organisations and local news outlets. The financial strains placed on news organisations in recent years has led to ‘news deserts’ in certain areas. If we are serious about reducing the impact of information disorder, supporting quality journalism initiatives at the local, regional and national level needs to be a priority.

- Roll out advanced cyber-security training. Many government institutions use bespoke computer systems that are incredibly easy to hack, enabling the theft of data and the generation of mal-information. Training should be available at all levels of government to ensure everyone understands digital security best practices and to prevent attempts at hacking and phishing.

- Enforce minimum levels of public service news on to the platforms. Encourage platforms to work with independent public media organisations to integrate quality news and analysis into users’ feeds.

What could media organisations do?

- Collaborate. It makes little sense to have journalists at different news organisations fact-checking the same claims or debunking the same visual content. When it comes to debunking mis- or dis-information, there should be no ‘scoop’ or ‘exclusive’. Thus, we argue that newsrooms and fact-checking organisations should collaborate to prevent duplications of effort and free journalists to focus on other investigations.

- Agree policies on strategic silence. News organisations should work on best practices for avoiding being manipulated by those who want to amplify mal- or dis-information.

- Ensure strong ethical standards across all media. News organizations have been known to sensationalize headlines on Facebook in ways that wouldn’t be accepted on their own websites. News organizations should enforce the same content standards, irrespective of where their content is placed.

- Debunk sources as well as content. News organisations are getting better at fact-checking and debunking rumours and visual content, but they must also learn to track the sources behind a piece of content in real time. When content is being pushed out by bot networks, or loose organised groups of people with an agenda, news organisations should identifying this as quickly as possible. This will require journalists to have computer programming expertise.

- Produce more segments and features about critical information consumption. The news media should produce more segments and features which teach audiences how to be critical of content they consume. When they write debunks, they should explain to the audience how the process of verification was undertaken.

- Tell stories about the scale and threat posed by information disorder. News and media organisations have a responsibility to educate audiences about the scale of information pollution worldwide, and the implications society faces because of it, in terms of undermining trust in institutions, threatening democratic principles, inflaming divisions based on nationalism, religion, ethnicity, race, class, sexuality or gender.

- Focus on improving the quality of headlines. User behaviour shows the patterns by which people skim headlines via social networks without clicking through to the whole article. It therefore places greater responsibility on news outlets to write headlines with care. Research[251] using natural language processing techniques are starting to automatically assess whether headlines are overstating the evidence available in the text of the article. This might prevent some of the more irresponsible headlines from appearing.

- Don’t disseminate fabricated content. News organisations need to improve standards around publishing and broadcasting information and content sourced from the social web. There is also a responsibility to ensure appropriate use of headlines, visuals, captions and statistics in news output. Clickbait headlines, the misleading use of statistics, unattributed quotes are all adding to the polluted information ecosystem.

What could civil society do?

- Educate the public about the threat of information disorder. There is a need to educate people about the persuasive techniques that are used by those spreading dis-and mal-information, as well as a need to educate people about the risks of information disorder to society, i.e., sowing distrust in official sources and dividing political parties, religions, races and classes.

- Act as honest brokers. Non-profits and independent groups can act as honest brokers, bringing together different players in the fight against information disorder, including technology companies, newsrooms, research institutes, policy-makers, politicians and governments.

What could education ministries do?

- Work internationally to create a standardized news literacy curriculum. Such a curriculum should be for all ages, based on best practices, and focus on adaptable research skills, critical assessment of information sources, the influence of emotion on critical thinking and the inner workings and implications of algorithms and artificial intelligence.

- Work with libraries. Libraries are one of the few institutions where trust has not declined, and for people no longer in full time education, they are a critical resource for teaching the skills required for navigating the digital ecosystem. We must ensure communities can access both online and offline news and digital literacy materials via their local libraries.

- Update journalism school curricula. Ensure journalism schools teach computational monitoring and forensic verification techniques for finding and authenticating content circulating on the social web, as well as best practices for reporting on information disorder.

What could Grant-Making Foundations do?

- Provide support for testing solutions. In this rush for solutions, it is tempting to support initiatives that ‘seem’ appropriate. We need to ensure there is sufficient money to support the testing of any solutions. For example, with news literacy projects, we need to ensure money is being spent to assess what types of materials and teaching methodology are having the most impact. It is vital that academics are connecting with practitioners working in many different industries as solutions are designed and tested. Rather than small grants to multiple stakeholders, we need fewer, bigger grants for ambitious multi-partner, international research groups and initiatives.

- Support technological solutions. While the technology companies should be required to build out a number of solutions themselves, providing funding for smaller startups to design, test and innovate in this space is crucial. Many solutions need to be rolled out across the social platforms and search engines. These should not be developed as proprietary technology.

- Support programs teaching people critical research and information skills. We must provide financial support for journalistic initiatives which attempt to help audiences navigate their information ecosystems, such as public-service media, local news media and educators teaching fact-checking and verification skills.